Facing Forward Together: Four Models for Organizing a Community for an Uncertain Future

Posted by Jason Bradford on February 25, 2009 - 7:48pm in The Oil Drum: Campfire

This is another contribution to Campfire from Michael Foley (user greenuprising). As a rather recent inductee to the process of community organizing, I found myself nodding along to this essay and wishing I had had this sort of background before beginning my work in Willits.

In a previous post, I argued that an important part of preparing at the local level for an uncertain future lies in strengthening our communities and making them more resilient. That takes community organizing, or making use of existing organizations. Mobilizing for policy change at both local, state/provincial, and national levels also requires organization. A few letters to the editor or cranky phone calls to your representatives won't cut it, though it may occasionally be personally satisfying. So how do we organize? And what sorts of organizations can we put to use? The following is an effort to lay out the basic models I've seen in action in the United States and Latin America. With minor differences, I suspect they're pretty much universal in the “modern” sector of societies around the world.

There are four basic models: NGOs (non-governmental organizations), community organizations, coalitions, and “coordinadoras” or “organizations of organizations.”

NGO's

NGOs (non-governmental organizations) are relatively small, professionalized advocacy and service organizations. They've proliferated over the last thirty years around the world and become major players in development, advocacy for the disadvantaged and oppressed, and the environment. They can be distinguished from other sorts of non-profits in their small scale and niche market characteristics: hospitals are big, permanent community institutions while health NGOs bring healthcare to refugees and displaced persons; schools and universities have established places in society while education NGOs sponsor early childhood education programs where there are none, conduct after-school classes for disadvantaged kids, or pursue adult literacy programs. Most environmental organizations, big and small, are NGOs. Obviously, there's lots of overlap between traditional non-profits and NGOs, but the difference should be clear enough.

NGOs are very adept at identifying community needs, coming up with solutions, and mobilizing funding. Mostly grant funded they generally have a good deal of independence from government and governmental red-tape. They employ professionals, many of them deeply committed to doing good and pursuing innovative solutions to societal problems. They can make decisions quickly and adapt to local circumstances.

[Caption: NGO graphic for the G8 Summit in Hokkaido, Japan last year]

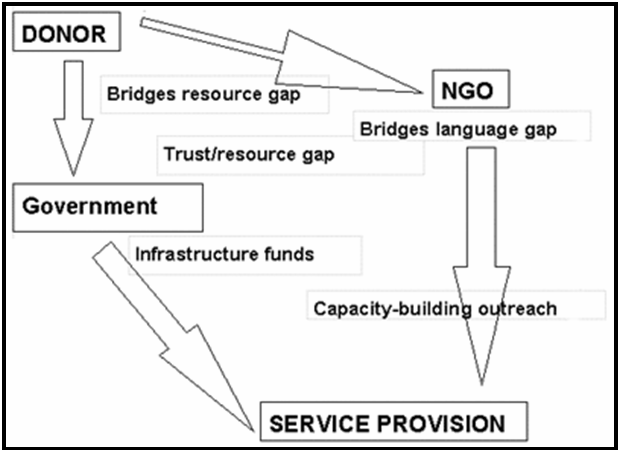

[Caption: One image of where service NGOs fit in society. Oops! Where are the rest of us?]

Some liabilities come with these advantages. NGOs are not generally democratic but hierarchical in structure internally, run by a strong director or CEO and overseen by an unelected (indeed, self-perpetuating) board of directors. They aren't formally accountable to the communities they serve. Their dependence on grant funding, moreover, makes them vulnerable to the whims of foundations and changing fashions in their field. In many cases, reputation with funders and among fellow NGOs can trump community service. Not being well-rooted in a particular community, they can flit from one trouble spot and one agenda to another, leaving little tangible behind; and they are often not good at mobilizing community support. For these reasons they are sometimes suspect in the eyes of community groups and government officials.

Community organizations

Community organizations are by definition membership organizations, though their constituency can be narrow or broad. As such they're rooted in the community and responsive to the needs, ideals, and demands of at least some community members. They have some claim to representativity and can use that claim before public bodies. They're democratically organized, at least in principle; and that, too, reinforces their claim to representativity. They often have a certain power to convoke public discussion and mobilize citizen action. And they pay their own way, through membership dues and fundraisers more than anything else.

Such organizations are essential to organizing a community response to the uncertainties of a global energy decline and “peak everything”. Bringing them aboard is the first step in bringing aboard the larger, harder-to-reach community. But that task may be complicated by some of the disadvantages of community organizations.

Traditional community organizations, for one thing, may be quite narrow in scope and active membership, sclerotic in leadership and action. Peak oil activists might attempt to take them over, but for them to really serve as a vehicle of outreach to the larger community the old guard will have to be brought along, and that will take time and finesse.

As an example: I belong to the local Grange. For those who don't know this organization, the Grange is a U.S. farmer's and rural community organization founded in the 1850's. It has the trappings of traditional fraternal societies but was very active as a center for agitation in the populist movement of the late nineteenth century. It has been supplanted among farmers by the American Farm Bureaus, representing the interests of mostly big ag since the 1930's, but it's still alive and important in many rural communities. My branch has been growing rapidly over the last few years, filled up with local food activists. But there's still a powerful old guard who vehemently defend what had become the central function of the organization, the monthly pancake breakfast, a community event for many old-timers and a traditional fundraiser. (Many a semi-moribund local branch of our Democratic and Republican parties has acquired a similar fetish over the years of party decline.) To them, anything that threatens the pancake breakfast, threatens the Grange. So, when a representative of a local NGO approached the leadership with grant in hand to renovate the kitchen and bring it up to commercial kitchen standards and run it as a communal kitchen, the old guard resisted. Never mind that the purpose of the Grange is to support local agriculture and local food production, never mind that the communal kitchen is supposed to promote “value added” production for local farmers and food entrepreneurs buying their product; the proposal threatened the central activity of the Grange. We're still working this one out, but the conflict illustrates both the difficulties of shifting course in a traditional organization and the problem of NGOs commanding community support.

Activists can also start community organizations from the ground up. These can be powerful vehicles, mobilizing new energies for new purposes. But they run up against some of the problems with community organizations. First, these are by definition membership organizations, therefore, almost by definition, dependent on volunteer labor. At the beginning, when enthusiasm is high, lots of people show up. Soon participation falls off, as people find that the hard slogging of committee work is not for them, or they run into irreconcialable differences with others in the organization. A few dedicated volunteers are left with the bulk of the work, and they not only face burn-out but a possible loss of community support. Efforts to revive sputtering organizations take imagination and lots of effort, but they can mobilize wider support and spark new projects. Continuity thus can be a problem in community organizations, especially where they attempt to carry out long-running projects. For this they are best served by a permanent staff, but few community organizations can afford such a luxury, and many fear (not unreasonably) that staff will end up dominating the elected leadership.

Second, the democratic process makes decision making slow and cumbersome. Organizations have to find decision-making processes that both honor their democratic character and don't get bogged down in endless meetings-of-the-whole – not an easy task. Individual organizations, moreover, cannot take on all the tasks, or wield all the influence, they would like to. This is where our third model, coalitions, comes in.

Coalitions

NGOs and community organizations form coalitions for a specific campaign – to push a new transportation policy, for example, or stop a major polluter. Coalitions don't run projects, they gin up public support for some change in attitude or policy. They help get others to take on projects they wouldn't otherwise do or stop projects they're committed to. Coalitions mean broad support and representativeness almost by definition, and that can translate into effective advocacy. And once a coalition is built, if things don't go disastrously, groups can come back together again for the next campaign and the next and the next.

[Caption: Anti-WTO protests in Seattle in 1999 featured a broad coalition of organizations, including labor unions]

Organizing a coalition takes effort, phone and people skills, and, of course, organizations that can contribute to a coalition. The most effective coalitions are often the broadest-based. If peak oil activists can get the Lion's Club, the biker's association, and the local churches behind a new county transportation policy, they've probably forged a winning coalition. Broad-based coalitions, however, take a lot of work. Activists with considerable powers of persuasion and lots of patience have to expend hours in educational work, and they need counterparts in the leadership of community organizations who are willing to listen. The concerns and limitations of each potential partner have to be taken into account, and group leaders have to be able to defend their participation to their memberships and boards.

Coalitions are also short-lived. They're good for specific campaigns but tend to come apart once the campaign is over. They're good at getting government to do things or raising funds for this or that good cause, but they can't run projects themselves. For this you need an NGO, solid community organization, or – the last category – an organization of organizations.

Organizations of organizations

By this I don't mean associations or federations. There are lots of these around, but they mainly provide services to their member organizations and advocacy on their behalf. The sorts of meta-organizations I have in mind don't have a name in English but turn out to be not uncommon. In Latin America, they're called “coordinadoras” or “redes” (web/network). In the United States, the most common examples are “ecumenical” or “inter-ministerial” associations, found in hundreds of towns and cities across the country. Some of these are just talking shops for ministers, but most were created to carry out projects that no one church could take on by itself. So we have ecumenical associations running housing projects, food banks, homeless shelters, adult daycare facilities, or clinics. Others provide an umbrella for the local Habitat for Humanity, Peace and Justice Center, Women's Center, etc. In either case, the organization combines the advantages of a permanent staff with community control (through member congregations) and lots of volunteer labor.

Another example comes from community organizing. Pioneered by the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) founded by Saul Alinsky, the model is used by four major national networks in lots of cities around the country. The main form of the model is a community organization of local churches, temples, and mosques. Participating congregations pay dues to support the efforts of an organizer whose job it is to develop community leaders from among the member organizations and help in generating an agenda for action. IAF has also carried the model to schools in the Southwest, involving parents, teachers and administrators around issues related to school and neighborhood needs. In both cases, organizers are careful to let leaders lead and the community generate its own agenda. The organization puts pressure on governments through political leaders but takes no part in political campaigns. Instead, it calls political leaders to account over the issues the community has identified as important and holds their feet to the fire until their demands are addressed. In some cases, it spins off permanent organizations to manage a project like housing or a public service.

[See pictures and brief description of an IAF green jobs project in Portland here].

This is a model, then, that has the advantages of representativeness of broad-based coalitions, with the long-term carrying capacity of an NGO or community organization. For those of us attempting to mobilize communities around peak oil issues, it could provide a powerful model. For example, such an organization could carry out concrete projects around local food security, while mobilizing citizens to push for more and better public transportation.

Even more than a coalition, such an organization takes significant effort to put together. It's not for nothing that the two prime examples are the work of professionals – ministers and other religious professionals in the case of the ecumenical association; trained organizers paid, initially at least, by a national community organizing agency in the case of congregation-based organizing. Even more than with coalitions, the concerns of individual organizations within the community have to be taken into account. The most successful example I encountered in Mexico had adopted a “one for all, all for one” formula for action: every member committed to support the organization's initiatives – which were themselves the product of consensus decision-making; the organization and its members, meanwhile, were committed to helping to further demands that were specific to one or another member organization. Considerable accommodation to member organizations may be necessary to make this model work. Or, as in the case of the congregation-based organizations, the community organization would have to be explicitly committed to steering clear of issues that were narrowly sectarian in character (abortion, for example). Either way, successful organizing depends on explicitly working out the relation between meta-organization and the member organizations.

Conclusion

There are lots of ways to skin a cat, as we say, or organize a community. Each of these models has its advantages; each has disadvantages or difficulties. The four models I've laid out aren't pure types. There are lots of hybrids out there, and it may make sense to try to forge a hybrid that shares the advantages of more than one model and avoids most of the disadvantages. I'd welcome especially comments that reveal new models or hybrids that have been particularly successful.

This was a link in Leanan's most recent DrumBeat post.

http://www.countercurrents.org/goodchild250209.htm

The question is how do we get past this?

That article should make any American's eart burn.

And look at how few posts on this thread - a thread about halitosis would have 100+ posts by now.

Precisely!

Indeed this question goes to the core of all humanity. Unfortunately the only real ideology is money since it is widely held that with that alone you can acquire everything and anything. This widely held belief will not change unless there is collapse of this system and people again learn to appreciate those aspects of life with real value. Just look at history, we humans aren't any good in prevention, especially when it involves long term, big issues. We have done everything we can to denigrate life on earth. The only thing we haven’t done is a nuclear war, probably because that much is that obvious. From the highest peaks of civilization (culture, technology, science) we have reached the deepest pits of human indignity (middle ages, wars, slavery, torture, environmental catastrophy) - time and again, over many millennia. What makes you think this time we are going to be any different? Can we change collectively our very own nature? Perhaps.

I think we have a good chance if we can balance the theory, the science, and the ideologies even, with the need of every single human being to be part of this effort. We have to inspire everyone in the smallest, most practical, everyday aspects of life. It is that simple yet, so important. We cannot expect change if change is not possible in all its different scales. Again looking at historical precedents even when ultimate powers can control almost everything and create their worlds of make believe they must first and foremost make every single one of us believe and then participate. The forces of power achieve that by offering the vision but most importantly the means for participation. After all it’s not the big oil companies that use up the oil and soil our earth; it’s me and you and my friends and your friends and their friends, friends. So a society that is all inclusive and thinks and acts in basic human principles is, to say the very least, more bonded, less vulnerable, more prepared, more sustainable. Again take another good look at history, athropology, society and observe the cultures and their characteristics that survived thoughout time.

Not trying to rain on anyone's parade but....

IMO one of the very key factors in rural communities, and city or suburb communities suffer from ills poster above described, ....one of the biggest factor is 'kinship'.

I guess this is rather self-evident but as to how it works is not readily apparent to most for they have become removed from any real roots long long ago.

Having a very mobile life and living in many locations tends to fray the threads of kinship, badly. Its very hard to 'go back home' when they don't even know you. And you are somewhat found to be tainted with very very different attitudes and viewpoints.

Believe me for I have been there. I am back at my place of birth but some here gave me a bit of a hard time at first. They would not trust me at all. My ancestors settled these very lands and I had kin folk all over the place....yet that shine of perhaps 'intellectualism' or being different makes a big difference in being once more accepted.

Yet after 20 years that has slowly dissolved. It took about that long. Only the older folks remembered me...and the younger ones...well now I get to look down at them and judge them as I was judged.

So community..here in the rural farm country is already in place but you may not find a place at the table unless you were actually born there and have kinfolks.

But with kinfolks nearby you are much more locked into this community. You need trust and that comes with being kin to someone who matters. Or can lend you help. Living alone and insular in the country can be very trying.

Now there are bad folks in every community. But they are very visible and the local 'word of mouth' is extremely efficient and active. Everybody knows everybody else's business and what they are up to.

Unless they are very shutmouth and then of course they are not to be trusted.

Let me offer and example. Today I am going to go see about getting a guy's electric hooked up. A friend of mine does all the bucket truck work for the town,since the town owns its own infrastructure. This other guy has had bad damage to his weatherhead and meter base and pole. They are not doing much for him since he has no reputation at all here, from a few counties away you see. But he sometimes drives a truck for another good friend of mine and he is going thru a bad divorce and has two small kids to handle. I was asked if I could expedite the work to get him hooked up since I had some favors owed by the electric guy and who yesterday asked me for a favor as well.

So I am going to 'call in' a favor and do this poor guy a favor by getting him expedited on hooking up his lines. I know he will never repay the favor. And I will have played out a favor. But his kids and a divorce I can understand. If I tell the electric guy that his base is good and wired right he will do the upper line work...all is ok then.

This is exactly how it works in small town and county outback USA.

Favors, friendship and kinfolk connections. Its alwasy worked that way. Always will. You have to be 'networked' in. Simple as that.

Airdale-the way I see community,and what has been in effect since this part of the country was settled AND....not belittling the efforts of this Key Post and those who see the need of community. Wish them luck.

My part of the country's like that, too, and was much more so, before the massive influx of hippies, artists, and others forced old-timers to accommodate. But people still tend to live in different worlds.

One approach, from an organizing perspective, is joining up. Community organizations hold the most active of the old-timers, they have a rep in the community and something of a constituency, and they often have resources like buildings and an income for community events. Join up. Bring like-minded others along and start the slow process of making over the old organization. It takes finesse, patience, and tolerance. Some will resist make-over and treat it like a hostile take-over. You have to work with that. You may have to take over, but do it nicely. But it can be worth it. As Jason says, some organization is better than none. Reaching some of the people is better than hiding in a cave.

I'll second that motion! I'd say something like the Grange, the Elks, American Legion or VFW, get your kids into Scouting, etc. Don't be put off by the right-wing reputation of some of these outfits, if you're a "real" person you'll find these places very welcoming.

I have lived in urban, rural, suburban, etc areas and basically from my own observations ALL Americans live alone, because the areas I have seen have been populated in a way that might as well be some huge being taking the whole populace, putting 'em in a big bag and mixing it really well, kinda like Shake-and-Bake, and then sprinkling 'em over the land, thicker in some areas, sparser in others.

I have seen a FEW cases of "kin" being around, and most "kin" are not like mine, they are not-so-good Americans and rather decent human beings, and they talk to each other and help each other.

I can't imagine a Bageant-esque area where social turmoil of the kind that moves people around, has been so low that there are "kin" everywhere. It must be great, even with the kind of feuds that are probably inevitable with any close group of humans (Malcolm Turnbull talks in The Forest People about one couple who just didn't get along well with anyone, so they'd build their hut off to the side).

We Americans have a hell of an uphill battle to get any kind of feeling of local kinship going again. It's going to take DOING things together, and we're not used to that.

Completely agree. I've been trying to 'get networked' into a village (in India) where I plan to move in. Everything you've said applies here as well: outsiders are generally untrusted until he starts proving he is harmless. But once the locals start trusting you, you become a local too.

People have so much time (its hard for city dwelling, busy-life people to imagine!) that they chit chat about each and everybody when they drink their 'chai' (tea) in the morning... and that chai drinking happens for 2 hours straight. They go back, look at their land - look for pests, etc., discuss about whose getting what pests and so on. Then they buy vegetables (locally grown). If anyone cheats, word-of-mouth just spreads. Infact, so much happens on trust.

These people laugh at me that I "buy" certain kinds of vegetables and fruits (bananas are never 'bought' over here because everybody has a plantain tree where the waste-water collects near their kitchen/bathroom (and yes, its all naturally sanitized)). People just walk into to each other's land, pick up a few fruits and eat. Of course, you are expected to allow others to walk in and take stuff as they wish. Again, this might be hard for a city-dweller to imagine. But its as simple as that - When everybody grows food - it doesn't matter whether I eat what grows on my land or on yours :)

Personally I keep helping with education to shift belief systems, however slowly, and I also provide tangible, "how to" type guides for the time when belief systems are crushed by reality and different behavior sets are required.

For the most part, I doubt more than a small percentage of the population will "get it" ahead of time, and even among those who do, they appear locked in structures in which behaviors don't align with stated goals and ideals.

Thinking probabilistically...having an organized group is much better than having none at all. Effectiveness is not guaranteed, but probability of a better outcome is higher.

We are getting requests from all over the US and even outside the US like New Zealand about the community revolution started in Portland.

Soil as value has been discovered by capitalists - get ready for lots of lawn sharing schemes to emerge.

Are you serious? I can see it now. Fidelity Select Soil Value Fund....;-)

Inevitable. That 'soil value' would be discovered by capitalists, who if I get your meaning still intend to transform the embodied ancient sunlight in soil back into money, repeating the process and and concentrating the wealth - ecosystem services equals the new 'leverage'! (EDIT - Actually, this has been happening already in stealth with industrial ag. The transfer of topsoil from the Plains states into the Gulf of Mexico has been an ongoing depletion fact suppressed by cheap fossil fuels. I expect that as energy profit from fossil fuels declines in aggregate, more individuals and communities will substitute labor for financial capital and generate small scale high EROI returns using natural capital (soil, sun and rain) - potatoes and root crops have 25-30:1 EROI.)

At least Portland is educating people about what is really important. That's why this first 2 months of Obama makes me sad. Instead of dumb rhetoric and missed opportunity we got with Bush after 9/11, we now get smart rhetoric and missed opportunity after credit crisis with Obama. It all points to we will need a different metric of what we compete for before things change.

POB and Nate; Sorry I'm not quite able to figure out what you are saying, but it sounds important.

Obama - Sad - Yeah, crying shame so far.

Uh-huh... Obama is in the same position as Jimmy Carter, and I expect similar results.

Carter was put in office by people expecting change, and what they got instead was an administration filled with Trilateral Commission and Council on Foreign Relations insiders. And their agenda was set by guess who.

Obama has been right on track so far, filling his administration with those who are already insiders and filling the role that has been predetermined for him. He knows what his boundaries are. It's about what I expected. See how his rhetoric on "free trade" vs American jobs has changed since the campaign.

At least he's more intelligent and comprehends the situation more than his competition.

Nate refers to the missed opportunities we're sseing with Obama.

In that connection, this quote struck me as ironic:

Obama himself was a community organizer, yet now what we need more than anything is for him to be called to account and have his feet held to the fire by the people who got him elected.

It seems like the last people he's interested in talking to these days are younger versions of himself.

Read the excellent book Topsoil And Civilization, soil IS wealth!

And the author points out that communal farming schemes, whether by slaves in Greece and Rome, farms in the USSR, serfs in Europe, you name it, did not work well. A person's own farm, or garden, is what it takes to get the kind of care it takes to do well - like working for someone else, farming for someone else means the average person will just do the minimum and then bug off home. The Hawaiians had land they had to farm for the local chief, then their own land, called their Kuleana, that was for their own food. Hence the old saying when I was a kid, "That's not my kuleana" meaning, That's not my business!

I would say the sensible approach is to resist all efforts by capitalists to commercially farm our front lawns and plow the local soccer field, with us working in it to pay off bank fees, or whatever evil scheme they cook up. Do things locally! If your neighbor wants to grow stuff in your land as well as his, and you're 89 years old and would rather just sit and knit socks, great. I've observed farmer's markets growing over the last few years, and that's one way to scare up some needed cash- locally.

Tell us more about the "community revolution" in Portland please. Is is more than what Michael discussed here?

And please specify which Portland you are referring to.

I say join your local Grange or form a new chapter.

Our grange mission ...

To Promote Local Agriculture, Environmental Stewardship, and a Vibrant Community.

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h854.html

Yeah I wanna check out the local Grange, the Granges are full of OLD people and they're the ones who grew up with canning, Victory gardens, etc.

This is an interesting article and fine as far as it goes. One of the underlying assumptions seems to be that the social structure will hold together in roughly the same fashion as it is right now. This is certainly a possibility but there are other possibilities too. Unfortunately, I do not expect there to be sufficient interest in probing those other probabilities to actually impact an existing community, thus we are left with approaches like this. By not considering the unthinkable, we will be left open to irrational responses if the unthinkable occurs.

Are the objections to "heirarchy" as opposed to democracy based on what's practical and effective, or purely ideological?

As the post says, some of the potential practical downsides - calcified, entrenched leadership; lack of real (as opposed to purely nominal) accountability; leadership bogged down in goals alienated from the original guiding spirit of the organization; drudgery of staff work - are common to both, while some - the cacophony of voices, the difficulty of making a firm decision, the endless reopening of policy and even principle debates - seem endemic to democratic structures.

I don't bring this up to say heirarchies are better. But I have no ideological prejudices regarding organizational structure. I want what's most effective, which is different in different cases.

I guess the question here is, are the kinds of people we'd be looking to interest in these goals and activate toward them so likely to have pro-democratic prejudices that for that reason alone any alternative structure becomes impractical, at least beyond a certain size?

This post also touches on something I've been thinking alot about - are existing organizations likely to be adequate for Peak Oil and relocalization activism? Or do we need completely new organizations? It seems there's a time difficulty in either case - it takes time we may not have to build something new, but it also takes that time to overcome/capture calcified leadership and rituals in existing structures.

(I suppose I do have my own "ideological" principle that the existing organizations have by definition been derelict in their responsibilities and have failed in their mandates, and should be superseded by completely new organizations.)

How do both of these questions relate to legitimacy? The post alleges lack of such legitimacy as an objection to heirarchy, but on the other hand concedes that a nominally democratic leadership can become just as alienated and illegitimate.

Similarly, it could be argued that most existing organizations are terminally mired in the fossil fuel worldview and are irredeemable, that this in itself cancels their legitimacy, and that legitimacy can only be restored by new groups which directly confront the challenges of energy descent and the relocalization imperative.

So my (tentative) conclusions are that legitimacy and accountablity, and effectiveness, are things which can only evolve organically through actions themselves, regardless of the political structure, which should be structured according to the requirements of the goal and not ideologically predetermined, and that the most likely vehicles are new organizations (perhaps initially using the platforms of existing ones for publicity, networking, poaching the worthwhile members who are looking for a more vigorous activism, etc.).

I'll admit to having a prejudice against hierarchy, but my observation (from years of looking at NGOs in Washington and Latin America) is that they're often inefficient precisely because of the hierarchy. In efficient, in particular, in building the sort of social movement that could really carry forward their stated aims. Instead, they focus on single "winnable" issues, concentrate resources on lobbying (Washington) or implementation of "projects" (Third World), and spend inordinate amounts of time trying to please donors and build their reps.

But, yes, I suspect we need something new, something on the line of the "coordinadoras"/organizations of organizations I described. Transition Towns Handbook outlines one approach that seems to have taken off in the UK and New Zealand and that people are getting excited about here.

I was all geared up to launch a transistion initiative in my town but this article just made me realise how futile my efforts may be. Maybe I'll just continue my geurilla gardening program of planting olive and nut trees through the city, leaving my Peak Oil calling cards in public places and leave the organizing to others.

I think the best way to go about this is to just lead by example. At first you'll look like a weirdo with the suburban doomstead, but when the preps start to pay off, maybe you'll have a copycat neighbor, and then it will start a domino effect.

I wrote something some years ago for a book that never got published. The link is: http://www.willitseconomiclocalization.org/files/well/OutpostGuideWillit...

Here's a piece:

One strategy to cope with the problems we face is to drop out of

society as much as possible and live a simple life, semi-isolated

from the horrors “out there.” However appealing this strategy may

be, global traumas will most likely catch up with all but the most

isolated recluse. Reversing course and implementing a complete

overhaul of our collective lives will require massive political will

and cooperative action. I am assuming that those reading this book

are more inclined to be politically active and work for social

change.

The trouble is, all of us who’ve grown up in the more affluent parts

of the world during the 20th century are behaviorally conditioned

by a super-abundance of highly disposable material goods, nearly

unlimited Earthly travel options, and community isolation. These

conditioned mind-sets are now part of law and institutional

structures reflecting the energetic glut on the upslope of the fossil

fuel era.

Truthfully, the bad news is that changing a highly institutionalized

culture is perhaps impossible by simply “changing mindsets or

values.” Mindsets and values are more often reflections of the

material conditions of a society. Frugality as a value follows

scarcity, for example, and conspicuous consumption follows

opulence. The good news, however, is that reality is conflicting

with dominant belief systems. This conflict sets up an opportunity

to help the disillusioned or confused by offering a coherent

explanation of what is happening, and pathways to realign their

thinking with the new environment.

History shows some instances when societies have responded

wisely, and plenty of other instances when they didn’t change in

time. So there’s no guarantee that this will be successful. But how

can we improve the odds?

Whoa! How come? This was supposed to inspire by getting us thinking about how. I actually see a lot of similarities between the "coordinadora" approach and the Transition Towns Initiatives.

Hi Michael,

There are two issues that I struggle with. The first is "coming out" publicly with the heresy of post consumer reconstructionism, when my family and friends are still firmly rooted to their ipods and plasma's.

The second issue I have is what you have identified in the quote above. I am already involved with a couple of groups and committees and I find that the more structured it is, the less seems to be achieved. There is still very little understanding of Peak Oil in our community, even among the climate chage zealots, that I fear a transistion initiative may be somewhat premature, even if I understand it is probabaly too late.

Questions that could be asked: Why do any of these organizations exist at all? Why does any group of people get together?

FMagyar mentioned above the article about the problem with inherent individualism in US culture. The fact that SOME people DO manage to overcome this and DO come together suggests that while this tendency toward individualism is a hurdle to be overcome, it is not a brick wall. In other words, organizing something is difficult, but not necessarilly impossible.

This furthermore suggests to me that there must be some self-selection going on. People who are open to joining organizations are probably already involved in something; people who would very much prefer to keep to themselves probably are not members of organizations. This in turn suggests to me that the membership of existing organizations is the best place to look when it comes to cultivating and recruiting people to join any new effort. This activity is best undertaken from the "inside", which in turn means that if one wants to organize one's community, the most promising strategy is to join and become actively involved in the organizations that are already operating within one's community.

I hate to say it but volunteerism is a hard sell.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volunteerism

It is easier to give money than one's time and effort.

It's easier if it's a religious duty.

I've talked to people about a Peak Oil mutual aid society but it has never been anything more than a social club.

It reminds me of the story of the Tower of Babel

except we all start out talking different languages.

Jason, I think you're making a distinction between NGOs and community organizations that don't exist. As part of an NGO that is explicitly a community organization, I can attest that this is the case! All of the organizations you identify in these categories are generally 501(c)(3) organizations, that is, tax exempt non-profit organizations.

I've been around both for a long time. In Mexico, I saw community organizations that had put together amazing initiatives without the help of NGOs, though there were a few NGOs ("professionalized service organizations) out there. Elsewhere in Latin America, El Salvador in particular, I saw NGOs everywhere, trying to sell the latest donor-funded project to communities and community organizations. There was a lot of cynicism, because NGOs came in and offered their composting toilets and smokeless cook stoves without asking people what their priorities were, ignoring existing community organizations in the process.

In D.C. it's if anything worse. The NGO's (call 'em advocacy organizations) may solicit funds from people they call "members", but members have no input; the professional staff, and even more, the donors, dictate direction. The NGO's pursue narrow agendas, one by one, with little to no effort to build or join social movements.

Don't get me wrong. There are clearly NGO's that do better. And there's a great deal to be said for having a staff and money to get things done, provide continuity, and think things through. But there's clearly a distinction between NGO's and organizations rooted democratically in their communities. The latter have some real handicaps, too, as I mentioned. So we have to think clearly about what we want to do and how we want to do it as we look for organizational vehicles to address Peak Oil issues.

Michael Foley

Thanks for this article; I think that an important enabler toward the creation of robust, resilient communities is awareness raising, so it's important to have more articles and discussions like these. I have an impression from reading TOD for a while that there's a continual increase of discussion about community as a crucial part of any effective adaptation to the new realities.

You mentioned the Transition Initiatives in a comment above; I think they will be very useful, and seem to be catching on. Not as a panacea, but one way forward. I particularly like the emphasis on continual trying and learning, and on fostering a positive attitude.

I've started a wiki that's intended to explore the "inner" issues of communities, looking at resources, challenges, etc.; see http://dwigki.wikispaces.com/On+Community. I'd like to see it become a collaborative effort involving folks from a variety of backgrounds. Unfortunately, it's languished for the last few months, as I've been consumed by personal and family issues. Even my community volunteering has had to be cut back. I'm starting to get a bit more free time, though, and have been doing some reading that I plan to fold into the project. I'd be interested in any feedback on it.

The wiki is a great idea. I'll go take a look and see if I can add anything. Another resources is http://www.transitionculture.org, the website of the transition initiatives.

Michael

It's interesting that you didn't address the most powerful way that we humans organize ourselves: through governments. Many local governments have taxing authority, regulatory authority, employees and land. They may have a bully pulpit through newsletters, televised meetings and such. There is a lot we can do through local government to prepare for declining energy.

In 2007 I ran for my local City Council on a platform that was heavy on the peak oil. My old website is still up at www.carlhenn.org. We had 11 candidates running for four seats, and I came in 5th, missing it by just 113 votes. I feel that a more competent candidate could have won on this platform, and indeed there have been some local officials who have run on this sort of platform and won.

دردشة بحرينيه |دردشة سعوديه |دردشة |دردشة خليجيه |دردشه اماراتيه |دردشة كويتيه |دردشة قطريه |دردشة عمانيه |دردشة اردنيه |دردشة فلسطينيه |دردشة عراقيه |دردشة مصريه |دردشة لبنانيه |دردشة سوريه |دردشة صوتيه | دردشة | - فله | - شات | - منتديات | فله - دردشه | منتدى | منتديات |

العاب